![]()

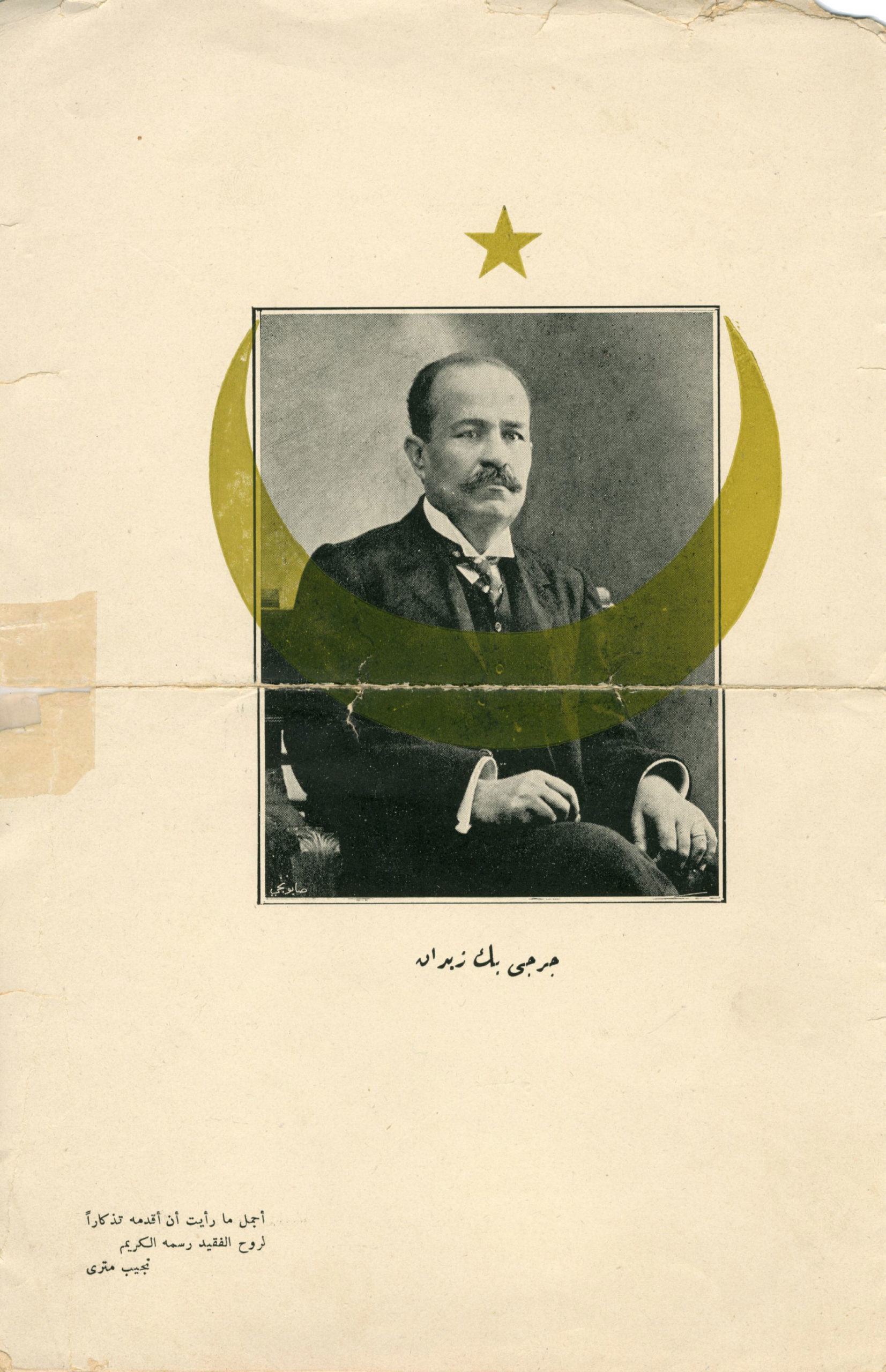

Jurji Zaidan’s Life Journey

George Choucri Zaidan

Remembers his Grandfather

[Published Al-Ahram – April 25th 2023]

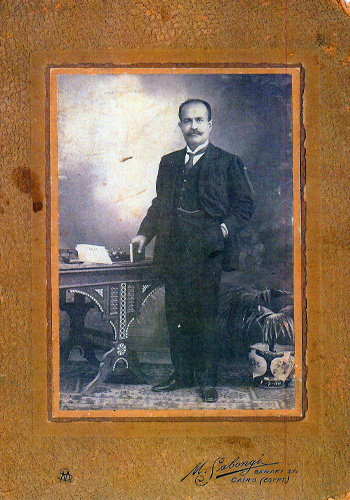

Jurji Zaidan was a pillar of the intellectual movement known as the Nahda (or Renaissance), which laid the foundations for a secular pan-Arab national identity. To this day he remains a household name across the Arab world for 21 phenomenally popular historical novels that, together with histories, helped give Arabs a sense of community through their shared history and a unique language. Eminently entertaining reads, they proved phenomenally popular to boot. Zaidan played many roles in the Nahda: historian, linguist, novelist, journalist, educator as well as political scientist and social reformer.

Born in 1861 in Beirut, Jurji Zaidan emigrated to Egypt in 1882, and died in Cairo in 1914. His phenomenal output was nothing short of astounding. He founded and for nearly 22 years (1892-1914) singlehandedly edited the great magazine Al-Hilal, during which time he was remarkably prolific. Zaidan wrote The History of Islamic Civilization (five volumes), The History of the Arabs before Islam, and The History of Arab Literature and Culture (four volumes), as well as three books on the history and philosophy of Arabic, one non-historical novel, an autobiography and several other books on a range of subjects. As Bishara Takla the founder of al-Ahram wrote: “Truly if the age of authors were measured by their output, we would have thought that the owner of Al-Hilal died at the age of one hundred whereas he left us at barely the age of fifty.”

Being Jurji Zaidan’s grandson has been a source of honor and humility. He died 25 years before I was born, so when asked if I knew him, I would routinely answer “no” without giving the question further thought. My professional life took me to the World Bank for 30 years to promote the economic and social development in developing countries. After my retirement I established the Zaidan Foundation in 2009 with the intention of informing the public in Egypt and abroad on Jurji Zaidan and his works. It was then that I realized I did know him after all, through reminiscences and values passed onto me by my father, Choucri, and my uncle Emile; and through witnessing how they built the Dar Al-Hilal publishing house into what it became and remains today. I also read what Jurji wrote about the secrets of his success in his autobiography and his Al-Hilal articles as well as the letters he exchanged with family and colleagues.

See the article published in Al-Ahram in Egypt in 2023 in English.

|

Read the article published in Al-Ahram in Egypt in 2023 in Arabic |

| Click here to read | Click here to read |

Zaidan, the son of an illiterate qahwaji (or coffeehouse proprietor), was born into the lower classes of Beirut; he was an autodidact and a self-made-man. His father forced him to drop out of elementary school to help him run his business. All of Zaidan’s learning was self-taught apart from two years in elementary school and one year in the medical school of the Syrian Protestant College which later became the American University of Beirut. He adopted middle-class values and his roots gave him a good understanding of his readers. He would credit this social sensitivity (al hassa al ijtimayeyyah) with much of his success as a journalist and writer.

Zaidan believed that self-realization and personal growth are the responsibility of the individual. He believed that character — will-power, integrity and rectitude — was more important than knowledge, education or heritage for worldly success. He credited his success above all to hard work, time consciousness and perseverance. Entrepreneurship and management, especially marketing, were hugely important attributes, and for journalists and writers this meant the ability to select interesting subjects and write objectively in a simple style. His honesty in word and deed won him the following and trust of a wide readership. Khalil Mutran eulogised him as follows: “I have not known a man that combined two such antithetical attributes — greatness and modesty.”

Zaidan emigrated to Egypt in 1882 because, in his first year as a medical student, he refused to submit to the diktats of the faculty at the Syrian Protestant College. When one of his professors was dismissed for teaching the theories of Darwin, he joined a strike. Thomas Philipp comments on this episode: “In the first meeting of the protesting students he was made chairman of the meeting. Zaidan hastened to explain he was chosen thanks to his conciliatory nature. But he emerged as one of two students of his class who refused to accept the conditions the college had set up for re-entry of the striking students and left the college never to return.”

My father, who was only eleven years old when Jurji died, used to often tell me that his father had a huge influence over him. I experienced this influence in various ways. My father’s favorite saying was al hilm sayyid al akhlak (“Equanimity is the greatest virtue”). In the world of journalism that meant personal considerations should not influence what was published. Intentions were never questioned and issues were treated as objectively as possible; personal attacks were banned. On more than one occasion my father told me that he and his brother decided Dar Al-Hilal would not publish a daily newspaper because this could easily become a political instrument and promoting an agenda would be contrary to the mantra that writers should be as objective as possible and “display truth and frankness without inclining towards any affiliation or party”.

Many interactions with my uncle Emile illuminated who Jurji Zaidan really was and what he stood for. Emile’s favorite saying “La yasih illa al-sahih” (“Only what is valid is valid”) was inscribed on a plaque on his desk. This is also the title of one of his articles in Al-Hilal (May 1912). The article conveys the importance of truth and honesty in personal and business relationships. One day when I was in his office, I asked Emile what the significance of the plaque was. He translated it with an English quote: “Honesty is the best policy”. This meant balance, perspective and good judgment; and sticking to the facts and the issues without letting words and arguments become substitutes for deeds. Constructive criticism from readers and others was sought out and published.

Towards the end of his life, during the Ottoman Constitutional Crisis of 1908, Zaidan reflected on what made a society distinctive and what made power legitimate. In a letter to his son Emile in 1908, when the latter was studying in Beirut, Zaidan argued against violent revolution against the Ottomans: “If the Ottomans had mandated the teaching of the Turkish language in all the Ottoman Empire,” which they didn’t, “our first loyalties may well have been towards the Ottomans rather than the Arabs.”

Al-Hilal was founded in 1892 and has been published continuously to this day — making it the longest-running magazine in the Arab world. Jurji Zaidan was its founding editor-in-chief, manager and printer. He strove to make it a popular periodical that would influence public opinion and help educate the people. At the time Al-Hilal was first issued, culture in Egypt was limited to literature. The new periodical gave it a wider and more comprehensive meaning. It included history, science, philosophy, sociology, politics and economics, thus merging intellectual thought with art, and science with philosophy. Zaidan believed in the importance of educating the whole of society in the broadest sense.

Zaidan also turned Al-Hilal into a platform for the works of distinguished authors, pioneers of Arabic literature, including giants like Husayn Haykal, Taha Husayn, Muhammad Farid Wajdi, ‘Ali Al-Jarim, ‘Abbas Mahmud Al-‘Akkad, Mustafa Lutfi Al-Manfaluti, Ahmad Amin, Gubran Khalil Gubran, Khalil Mutran, May Ziadeh and many others. And all this made al-Hilal a towering and unique institution of journalism.

Towards the end of his life, during the aforementioned Constitutional Crisis, Zaidan reflected on what made a society distinctive and what made power legitimate. But for the most part Al-Hilal remained a cultural project and did not engage in political discourse. His non-confrontational nature and his belief that writers should be as objective as possible without leaning towards any affiliation or party kept him in the intellectual realm and away from political activism.

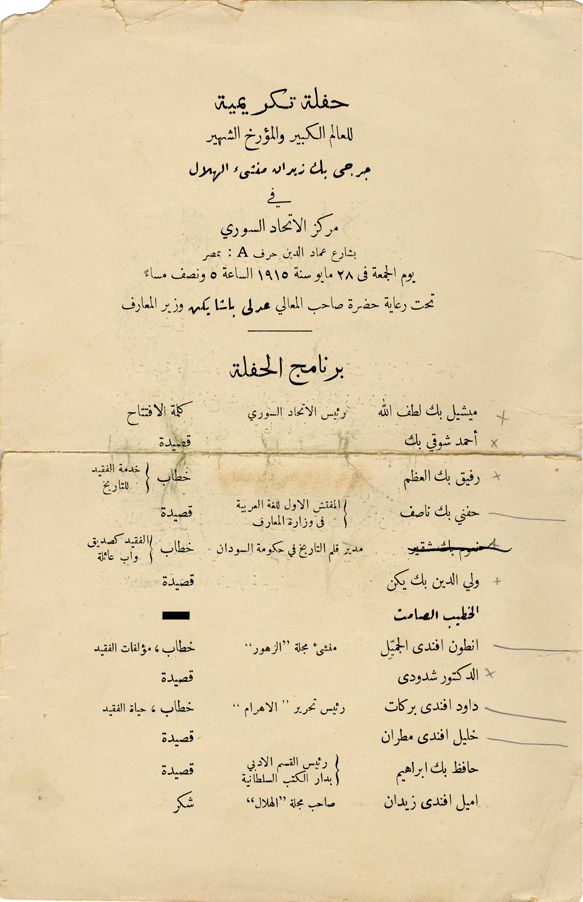

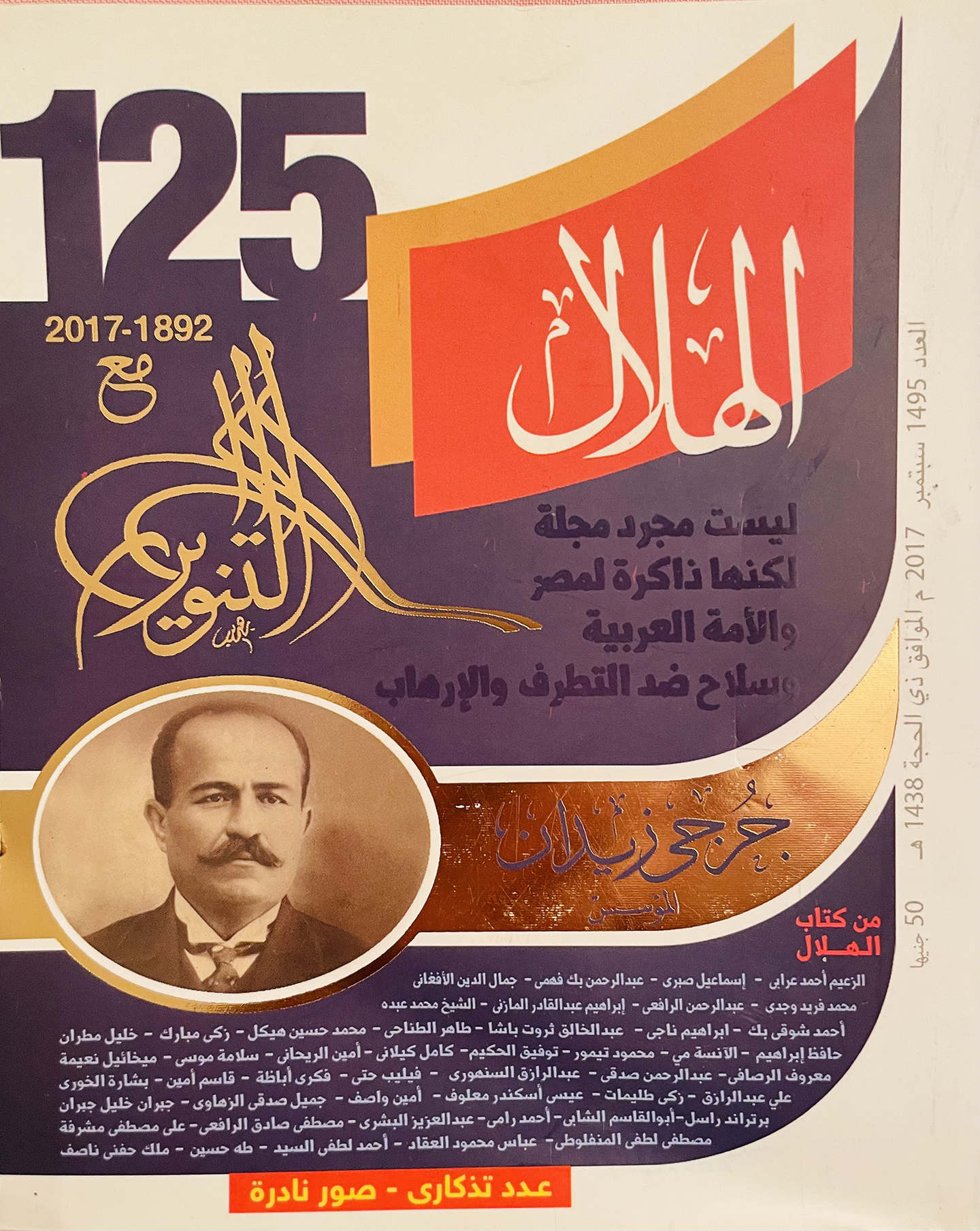

To this day Al-Hilal reflects everything Jurji Zaidan stood for. It remains a beacon of knowledge in all fields: intellectual honesty and truth in discussing complex issues; moderation in discussing political and social issues; and opposition against extremism and terrorism — in short, the cultural heritage of the Nahda. Special issues of Al-Hilal celebrated its centennial in 1992 and its 125th and 130th anniversaries in 2017 and 2022. Nothing better illustrates Zaidan’s legacy than the cover of the 2017 issue, which says: “Al-Hilal is not only a magazine but a repository of the history of Egypt and the Arab nation and a bulwark against extremism and terrorism.” As for the cover of the 2022 issue, it proclaimed: “Al-Hilal: Still Writing History.”

Following Jurji’s death in 1914, his two sons, Emile and Choucri Zaidan turned Dar Al-Hilal into a pioneer in launching new types of magazines. By the time Dar-al-Hilal was nationalised in 1961 it had launched: Al Mussawar, the first illustrated weekly magazine in 1924; Al-Kawakeb, the first weekly magazine for films; Hawaa, the first weekly magazine for women; and several weekly magazines for children starting with Samir. Dar Al-Hilal has also had several monthly publications: Riwayat Al-Hilal (Al-Hilal Novels); Kitab Al-Hilal (The Al-Hilal Book); Tabibak Al-Khaas (Your Personal Doctor); and others.

As Dar-al Hilal made major contributions to the development of journalism in Egypt it also became a de-facto “school of journalism”. Many well-known journalists and owners of publishing houses started out at Dar Al-Hilal. Najib Mitri founded Dar Al-Maaref after his association with Jurji Zaidan; Mustafa and Ali Amin worked many years at Dar Al-Hilal before they founded Akher Sa’a; Anwar Al-Sadat – the third president of Egypt – worked briefly at Dar Al-Hilal writing articles in its magazines before he founded Al Goumhouriya. Many well-known writers held jobs as editors of its magazines, among whom were Fikri Abaza, Ahmad Bhaa Al-Din; Youssef Al-Sibae and Makram Mohamed Ahmed — the last two became chairmen of Dar Al-Hilal.

Zaidan’s instrument was the pen, and he pioneered the historical novel as a new genre of Arabic literature. His 21 novels about Islamic history were serialized in Al-Hilal. Set in the context of historical events from pre-Islamic times to the end of the Ottoman Empire, they educated the public about their heritage, culture and history. Whereas writers like Walter Scott and Alexandre Dumas only used historical settings for their characters, Zaidan used the novel and its characters as a way to teach history. His novels were less concerned with exploring human frailties and sensibilities than they were with setting out historical events. He described his approach as follows: “the reader learns about historical facts while he thinks he is reading an entertaining story.” He achieved this in prose that makes him a remarkable stylist, hailed by his great contemporary Mustafa Lutfi Al-Manfaluti as “simple and clear though difficult to replicate”.

Zaidan’s historical novels contributed to the development of a new Arab consciousness and identity and to the secular nationalism of the Nahda. Taha Husayn assessed his contribution in these terms: “The historical novels that Zaidan published had the most important impact which enabled the Nahda to bear fruit that readers of today still enjoy.”

The novels remain popular to this day throughout the Arab world and also in countries with large Muslim populations. They are also popular in the West. Zaidan’s novels have been translated into many languages including Persian, Turkish, Uighur, Urdu, Indonesian, Kurdish and Azeri as well as English, French, German and Spanish. They are republished every decade or so in the Arab world in Egypt, Lebanon and Tunisia. His History of Islamic Civilization was translated into English, Urdu, Turkish and Persian.

Zaidan wrote widely on Arab and Islamic history and on the Arabic language, the basic foundations of Arab cultural and national identity. He was a major advocate for the creation of Cairo University, the first university to be established in Egypt in 1908, and for the establishment of the Majma’ Al Lughawi, a language authority modelled on the Académie Française.

He had a remarkably productive professional life. In barely three decades, he went from ambition to achievement and from humble beginnings to the heights of recognition. He made a profound impact on the culture of his people, the history of his region, and the literature of his language. His work helped to forge the modern Arab identity, found the modern mass media of his era, educate the masses and bring culture to the broad public. Such is the legacy he bequeathed to the world.

In 1992, the Egyptian government commemorated the 100th anniversary of the establishment of Al-Hilal and by commissioning an opera about Zaidan’s life, Hilal Masr (Egypt’s Crescent), produced by the Ministry of Culture and attended by President Hosni Mubarak along with top government officials and prominent Egyptian and Arab figures. The government also issued a commemorative Al-Hilal stamp and minted a silver one-pound coin with the portrait of Jurji Zaidan. In 2012, in recognition of Al-Hilal’s contribution to Egypt’s cultural development, the Library of Alexandria digitised the complete Al-Hilal issues from 1892 to 2007 as part of its project on the Memory of Modern Egypt.

My own modest contribution to keeping the memory of my grandfather alive is the Zaidan Foundation, established in 2009 to enhance intercultural understanding between the Western and Arab-Islamic cultures. Misunderstandings between the two worlds often begin and are greatly magnified by limited or erroneous knowledge. The Zaidan Foundation’s website, launched in 2012, honours the legacy and works of Jurji Zaidan; it is designed to be a resource for scholars and readers all over the world, including important works in Arabic, English and French by and about the great man. One hundred and fifteen years’ worth of Al-Hilal issues and eleven historical novels can be read in Arabic, so can all the major books Zaidan wrote on language and his autobiography. Four major works on Zaidan’s contributions can be read in English and French. Nine novels translated into French and six into English are also available. Hilal Masr and other videos about Zaidan can also be viewed on the website.

George Choucri (Shukri) Zaidan is an economist who directed the World Bank department that covered the Middle East and supported Egypt’s economic and social development. He founded the Zaidan Foundation ( www.zaidanfoundation.org ) in 2009.

Watch this exciting video about Jurji Zaidan’s life

![]()

His Early Life

Jurji Zaidan was born in Beirut, Lebanon, on December 14, 1861 into a Greek Orthodox family and he grew up in very modest conditions. By the time he died unexpectedly in Cairo on July 21, 1914 at the age of fifty three he had established himself in a little over twenty years as one of the most prolific and influential thinkers and writers of the Arab Nahda (Awakening), an educator and intellectual innovator in the Arab world. He could not complete his autobiography1, started only a few years before his untimely death. It covered only the first twenty years of his life but it gave us an invaluable insight into his early years in Beirut and what drove him and enabled him to scale the heights that he did.

Zaidan received a rudimentary education as his father sent him to work in the small family restaurant from age eleven. Zaidan senior, himself illiterate, did not encourage any education beyond simple reading and writing. But his son had a thirst for knowledge and education which his mother encouraged. With the help of teachers that he met in the family restaurant he pursued his studies at home. At the age of nineteen Jurji was able to successfully sit for the entrance exam of the Syrian Protestant College that was to become the American University of Beirut and enrolled in its school of medicine. But his studies came to an abrupt halt because of a strike resulting from a schism between the administration and some teachers over the firing of a faculty member for having expressed favorable views about the theory of evolution. The young Zaidan was a student leader and a strong proponent of reinstalling the professor in his position. In the ensuing turmoil, the administration closed the University for a year which prompted Jurji to leave for Cairo in 1882. Once settled there Zaidan began a long career as a writer and journalist.

He was a self-made man. In his autobiography he frequently uses terms such as “hard work”, “perseverance”, “punctuality”, and “discipline”. In his letters to his son Emile, Zaidan writes how reading “about the life of men who reached the top through their efforts and struggle and reliance upon themselves alone” excited him so much, that he was never able to put down the book before finishing it. He felt the stories he read reflected exactly his own situation, providing advice on how to rise above the conditions of one’s birth.

![]()

Autobiography

Jurji Zaidan started to write his autobiography a few years before his unexpected death at the age of 53. He was unable to complete it. It covered only the first twenty years of his life and ends when he leaves Beirut to start what was to become a new life in Egypt. But it tells a lot about the man and the inner strivings that drove him to become one of the leaders of the Arab Renaissance.

The autobiography was translated by Thomas Philipp as part of his book on Gurji Zaidan. His Life and Thought. Wiesbaden, Germany: Steiner Verlag, 1979 for which he wrote an introduction. It is followed by selected letters on subjects that were dealt with in his autobiography and that Zaidan wrote mostly to his son Emile while he was studying at the American University in Beirut.

![]()

Many Men In One Man –

Joseph Harb

Jurji Zaidan was a prolific writer whose objective was to inform and educate his Arab contemporaries about the modern world, as well as about their past and their national identity. He is considered to have been one of the intellectual leaders in laying the foundation for a pan-Arab secular national identity. Zaidan was the archetypical member of the Nahda at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He belonged to a new intellectual elite whose education was not based on traditional or religious learning. Zaidan was an autodidact whose only college training was one year spent in the medical department of the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut. His writings as a historian, as a linguist and as a political and social commentator and analyst bore the strong imprint of his scientific and evolutionary outlook and shaped his analytical approach in all these areas. His works gave a distinctly secular outlook to the emergence of the Arab nationalism of the times. Many other Arab writers both Muslim and Christian like himself promoted similar political and social values, but he was one of its leaders.

Zaidan was once described, quite appropriately, as “many men in one man” as he established himself as a successful historian, novelist, linguist, educator and journalist. His writings in all these areas were used, in a mutually re-enforcing way, to develop and promote a national sense of pan-Arab secular identity.

The Journalist

In 1892 he founded one of the earliest and most successful monthly magazines called Al-Hilal (The Crescent Moon) which has been published without interruption to this day. Al-Hilal remains a treasure trove for the student of intellectual and social history of the time. The twenty-two historical novels he wrote were all serialized in that magazine. In addition to the novels, he also wrote articles in his magazine on a large number of topics: the history of Islamic civilization, and the history and development of languages, as well as on political, social, educational and ethical issues. He thus played a very important role in making readers of Arabic more aware of the important events in their history and in developing a sense of national identity. Dar al-Hilal is still today one of the largest publishing houses for periodicals in the Arab world.

Nothing better illustrates the legacy of Jurji Zaidan’s contribution to the Arab cultural heritage than the cover of the Al-Hilal issue of 2017 celebrating the 125 th anniversary of its birth in these words: “Al-Hilal is not only a magazine but a repository of the history of Egypt and the Arab nation and a bulwark against extremism and terrorism.”

The Novelist

Zaidan may be best remembered today as one of the pioneers in the composition of historical novels within the modern Arabic literary tradition and in their serialization in magazines. The twenty-two historical novels he wrote are popular to this day – they were regularly reprinted every decade or so since they were first serialized and more than one hundred translations of these novels have been made into many different languages including Persian, Turkish/Ottoman, Javanese, Uighur, Azeri, Urdu, French, Spanish, and others. The novels cover an extensive period of Arab history, from the rise of Islam in the seventh century until the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th. The particular manners, lifestyles, beliefs and social mores of those periods, as well as political events, provided the context within which Zaidan weaved adventure and romance, deception and excitement. They were therefore as much “historical” as “novels” reminiscent of the historical novels of Alexandre Dumas in France and Sir Walter Scott in Britain, though Jurji Zaidan’s novels more closely reflect actual historical events and developments.

The Historian

Jurji Zaidan wrote several books on history and perhaps his most noteworthy contribution was a five volume work on the History of Islamic Civilization2 in which he attempted to provide, for the first time, a secular national interpretation of Arab history, related and yet distinct from the traditional Muslim religious interpretation of the past. In this context he wrote a book about the early history of the Arabs before Islam.

2 The fourth volume, Umayyads and Abbasids was translated into English by D.S.Margoliouth in 1908 and is available in the Library of Congress, the British Library, the Harvard (Widener) Library and others.

The Linguist

Jurji Zaidan wrote several books on linguistics and had a major role in influencing the evolution of the Arabic language during his time. At the theoretical level he analyzed the attributes of various languages and their evolution, judging Arabic to be one of the more developed languages. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who believed Arabic to have reached a static ideal in the Koran, he saw Arabic, just like other languages, to be a “living being” that had evolved over time and needed to change to integrate modern, scientific and other terms. As an Arab nationalist he strongly felt that classical rather than colloquial Arabic should be the vehicle for this modernization thereby becoming an even stronger bond strengthening all Arabic-speaking peoples. He worried that using local Arabic dialects for that purpose would erode and divide the Arab world just as the evolution of Latin into European languages spawned competing nationalisms. He was especially concerned about spreading education to as many people as possible – as his efforts for the establishment of a simplified, modern, standard written Arabic show. At the practical level he was one of the most vocal proponents for the establishment of an academy to steer the process of modernization of the Arabic language comparable to the Académie Française. Partly as a result of his efforts, an equivalent institution, the “Majma’ al Lughawi”, was established.

The Educator of Society

All the above roles combined to further Jurji Zaidan’s mission to educate the Arabs about their shared past and at the same time instruct them about the modern world thus creating a national consciousness and identity. He wrote extensively, mostly in al-Hilal, on a wide range of social and other issues. These articles dealt with, not only topics on history and language that were covered more extensively in his written books, but also a variety of social and political subjects. Areas covered in these writings included such topics as the relationship between religion and science, ethics and society, the role of women, morality, work ethics among others3. He was a strong supporter of the social emancipation of women but within the respect of her traditional role in the family. Last but not least, he was one of the strongest proponents for, and instrumental in, the establishment of the first Egyptian University.

3 For a selection of Jurji Zaidan’s selected writings that were translated into English see the volume by Thomas Philipp on Jurji Zaidan and the Foundations of Arab Nationalism. The Table of Contents of that Volume reproduced in this website under “Studies on Jurji Zaidan” lists the titles of these articles and book excerpts.

Click here to read Joseph Harb’s essay in Arabic

Jurji Zaidan’s name can also be spelled: